|

“Who

will teach me what is most agreeable to God, so that I may do it?”

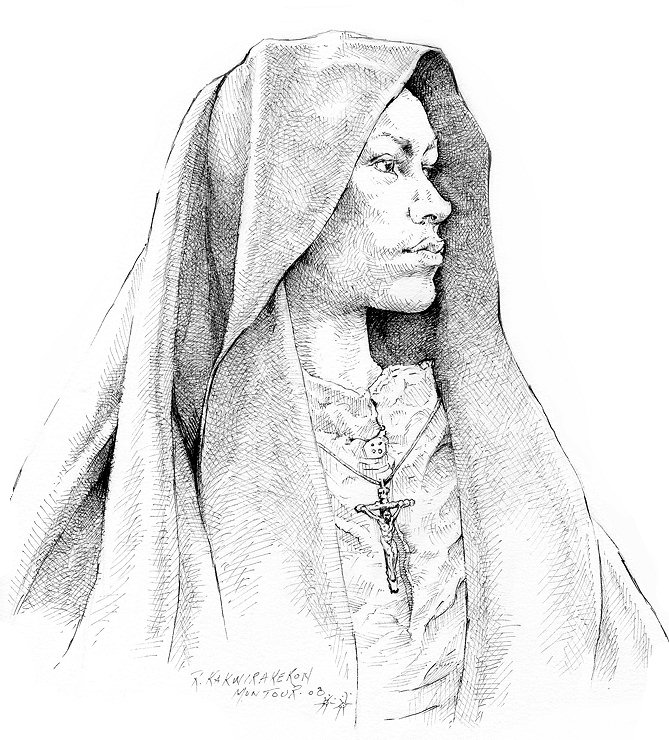

Presented at the 30th Conference on New York State History, Káteri Tekahkwí:tha  © 2009 R. Kakwirakeron Montour A Lily Among Thorns The Mohawk Repatriation of Káteri Tekahkwí:tha by Darren Bonaparte June 5, 2009, in Plattsburgh, New York Introduction Blessed Káteri Tekahkwí:tha, the Lily of the Mohawks, was a Kanien’kehá:ka woman of the 17th century whose extraordinary life and reputation for holiness have made her an icon to Roman Catholics throughout the world. She was declared venerable by Pope Pius XII in 1943, and beatified by Pope John Paul II in 1980. In 2008, the Cause for the Canonization of Blessed Káteri Tekahkwí:tha was formally submitted to Pope Benedict XVI. She is memorialized at Saint Patrick’s Cathedral in Manhattan and the Washington National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. Throughout North America, she is depicted in statues and stained glass windows that adorn chapels named in her honor. A recent biographer declared that no aboriginal person’s life has been more fully documented than that of Káteri Tekahkwí:tha. The writings of Jesuit priests who knew her personally became the basis for at least three hundred books published in more than twenty languages. 1 Reverence of Káteri Tekahkwí:tha transcends tribal differences. Indigenous Catholics identify with her story, and have taken her to heart. They have made her so much their own that they depict her in their art wearing their own traditional clothing. The only negative in all of this is that she looks less Mohawk with each new depiction, as though her cultural background is irrelevant. The opposite is true: Káteri Tekahkwí:tha was raised with—and defined by—traditional Mohawk beliefs, and it was her understanding of them that led her to embrace a new faith, not so much as a rejection of her traditional beliefs, but as the fulfillment of them. In recent decades, scholars like David Blanchard, K. I. Koppedreyer, Daniel Richter, Nancy Shoemaker, and Allan Greer, among others, have wrestled this subject away from the domain of more devotional writers, bringing a more critical insight into the cultural world of Káteri Tekahkwí:tha and the Rotinonhsión:ni converts of Kahnawà:ke. The time has come for the Rotinonhsión:ni to take it to the next step by repatriating the story of the Mohawk maiden and liberating it from the “saint among savages” theme that was attached to it so long ago. The Life of

Káteri Tekahkwí:tha

The 17th century was the age of contact and colonization for the Kanien’kehá:ka, the People of the Land of Flint. With the arrival of Champlain and Hudson, The Prophecy of the Serpents of Silver and Gold was fulfilled before our very eyes. The Kanien’kehá:ka were part of a confederacy known as the Rotinonhsión:ni, the “People of the Longhouse,” also known as the Five Nations and the Iroquois. To negotiate a treaty of peace and friendship with the Longhouse, Dutch fur traders of New Netherland had to go through the Mohawk, the “Keepers of the Eastern Door.” Wampum belts depicting this covenant sometimes have two human figures holding a chain between them. The European is holding an ax in his other hand, representing both trade and military alliance. For the Rotinonhsión:ni, the covenant with New Netherland meant conflict with the aboriginal allies of New France, the Huron and Algonquin. Káteri Tekahkwí:tha witnessed firsthand the “clash of cultures” brought about by the colonization of Turtle Island. She was a product of it. Her mother was a Catholic Algonquin captured during a Mohawk raid on Trois-Riviere, adopted and nationalized as a Mohawk, and married to a chief. Tekahkwí:tha was their first child, born sometime around 1656. The smallpox epidemic of 1661-1662 killed her parents and a younger brother, and left her disfigured, sickly, and unable to stand bright light. The name Tekahkwí:tha, in fact, is a reference to the way she used her hands to feel her way. In the aftermath of this tragedy, she was taken in by an uncle, a leading chief of the village, and raised as one of his daughters. While his wife made plans to arrange a marriage for the little girl, the chief concerned himself with the affairs of the nation. Mohawk attacks on their Huron trading partners had long been an irritation to the French, and a new governor arrived in New France, as one Jesuit wrote, “to plant lilies on the graves of the Iroquois.” 2 The Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga and Seneca entered into peace talks with the French, but the Mohawks refused to be a part of it. The French sent an army to Mohawk country in January of 1666, but they got lost in the woods near Schenectady, and were forced to abandon their ill-conceived mission with great losses. Several months later, they launched another assault with an army twice the size of the first. With the herald of war drums to announce their approach, they succeeded in marching straight into our villages and burning them to the ground. We were able to evacuate before they arrived and were seen shouting at the French troops from a nearby hilltop, but we could do little to halt the progress of the Carignan-Salières Regiment. The French commander marveled at the material prosperity evident in the Mohawk villages. It is said the French army found enough food in these villages “to nourish all Canada for two years.” 3 Tekahkwí:tha was then ten years old and living in the eastern Mohawk village, Kahnawà:ke, or “At the Rapids,” the first to be destroyed by the French. The burning of her village must have been particularly traumatic to a child, but her Jesuit biographers rarely mention it. Somehow we managed to survive the winter. We were probably taken in by our brother nations. In the spring, we built new villages on the north side of the Mohawk River, just in time for the French to send peace envoys in the form of Jesuit missionaries. At first the Jesuits tended to our Christian Huron and Algonquin captives, but Mohawks began to take an interest in their teachings as time went by. With missions established in all of the Five Nations, a steady flow of Iroquois converts began to depart our homelands for Kahentà:ke, a new Indian mission across the river from Montreal at Laprairie. The success of this mission caused one Jesuit to remark, …in less than Seven years

the warriors of Anié have become more numerous at montreal than

they are in their own country. That enrages both the elders of

the villages and the flemings of manate and orange. In a short

time, less than a year or two, 200 persons were thus added to the

number of the Christians at la prairie. 4

The Mohawk population had already suffered significant losses to disease and warfare, and on-going conflicts on other fronts meant the Mohawks had no souls to spare. Yet there was a good argument for having eyes and ears in the heart of New France, where we could watch troop movements should hostilities resume. It also gave us another market for furs, giving us leverage with the English, who by this time were running the old Dutch store under the name New York. Jesuit accounts emphasize religious differences between the Mohawk converts and their traditional kin as the primary reason for the removal. The schism seems to have affected the home fire of Tekahkwí:tha in particular. Her uncle was one of the village elders opposed to this exodus to New France. When the renowned warrior Atahsà:ta—better known as Kryn, the Great Mohawk—left for Kahentà:ke in 1673, more than 40 people went with him, including Tekahkwí:tha’s older sister. The chief was not about to lose another daughter, so he forbade Tekahkwí:tha from going near the missionaries. One autumn day in 1675, Father James de Lamberville, a newly arrived priest, walked by what he thought was an empty longhouse and felt impelled to look inside. He found Tekahkwí:tha there with a foot injury. The 19-year-old was a good candidate for instruction, so he spoke to her of Christianity, and urged her to come to Mass. She was baptized on Easter Sunday of 1676, and given the name Káteri, the Mohawk version of the French form of Katharine. It is by the combination of her Catholic and traditional Mohawk name that we know her today, Káteri Tekahkwí:tha. Around this time her new parents arranged a marriage for her, but she refused to go along with it. The Jesuits tell us Káteri was persecuted for becoming a Christian, and had stones thrown at her by children. They also claim that her uncle had a warrior enter her lodge and threaten her with a tomahawk, but she only bowed her head as if to accept her fate, spooking the young warrior. The story gets more dramatic with each telling, with the terrified warrior fleeing for his life as if pursued by demons. She would not endure these trials for long, as her older sister sent her husband on a dramatic mission back to the Mohawk Valley to bring Káteri to New France in the fall of 1677. With the assistance of Father Lamberville, Káteri was spirited away from the Mohawk village by her brother-in-law and a Huron of Lorette. Káteri’s uncle returned home to find her missing and set out in hot pursuit. The men were aware of his approach and hid Káteri in the forest. They convinced her uncle that they were hunters and not the individuals he was looking for, nor had they seen a young woman. Although the Jesuits state that the uncle was in a homicidal rage when he began the chase, he calmly turned around and went home. Káteri and her companions proceeded on foot to Lake George, where they recovered the canoe the rescuers hid there on the way to the Mohawk Valley. After a journey of about two weeks on the Lake George/Lake Champlain/Richelieu River corridor, they reached the new Indian mission, St. François Xavier du Sault, established several miles west of Laprairie at what is now Ville Sainte-Catherine. Like the Mohawk village from which many of its people came, there were rapids nearby, so it was given the name Kahnawà:ke, the name by which it is known today. After a long and harrowing journey, Káteri arrived at her new home. During the tour of the new Kahnawà:ke, she would have been taken to the chapel, which at that point looked more like a bark longhouse than a church, but it did have a proper altar with monstrance, chalice, paten, and candelabra. There was also a wampum belt of over 8,000 beads, a recent gift of the Hurons of Lorette to the people of Kahnawà:ke. Father Claude Chauchetière wrote of this wampum belt in his history of the Mission of the Sault, which we find in the Jesuit Relations: It was a hortatory collar

which conveyed the voice of the Lorette people to those of the Sault,

encouraging them to accept the faith in good earnest, and to build a

chapel as soon as possible, and it also exhorted them to combat the

various demons who conspired for the ruin of both missions. This

collar was at once attached to one of the beams of the chapel, which is

above the top of the altar, so that the people might always behold it

and hear that voice. 5

Replica

of the Huron wampum belt given to Kahnawà:ke Mohawks in 1677.

Reproduction and photograph by the author. Káteri moved in with her older sister’s family, and took instruction from an older woman named Kanáhstatsi Tekonwatsenhón:ko. This was a woman she knew from childhood, a long-standing Christian. Kanáhstatsi became a third mother to Káteri. When it came time for the winter hunt, she went with her sister’s family out into the wilderness. There were several other families in this hunting party. One night an exhausted hunter came in after everyone else had gone to sleep. He found an empty space on the floor of the lodge and fell fast asleep. His wife woke up the next morning and saw that he was lying next to Káteri. She convinced herself that the two of them were having an affair, and accused her of it to the priest when the hunting party returned to Kahnawà:ke. Káteri was questioned about it and acquitted herself well in the matter. The priest believed her, but she swore off winter hunts after that. Káteri made a new friend the following spring, a young Oneida widow named Wari Teres Tekaien’kwénhtha. They met while visiting the construction site of the new wooden chapel after the carpenters had left for the day. Káteri and Wari Teres became inseparable friends, each of them supporting the other in a celibate life devoted to Christ. They even spoke to a Huron woman about starting their own convent. When Káteri’s sister and Kanáhstatsi put pressure on her to get married, she refused. She knew that French nuns were consecrated unto Christ, and decided that was the life for her. On March 25, 1679—the Feast of Annunciation—she made a vow of perpetual virginity. This brings us to the part of the story that many of the later books gloss over or omit altogether. According to Jesuit accounts, the Onkwehón:we Tehatiiahsóntha’—“Original People Who Make the Sign of the Cross”—somehow found out that the Jesuits would scourge themselves in private, and wanted to participate in this hidden aspect of Christianity. They imitated and exceeded the Jesuits in this regard. Not only did they whip themselves repeatedly, but they walked barefoot through snowdrifts, and cut holes in the ice to submerge themselves in water up to their necks long enough to say the rosary. The most fervent would wear a cingulum, or “penitential girdle,” a leather belt with metal studs on the inside that dug into the wearer’s skin. The Jesuits made half-hearted admonitions against all of this, but they secretly admired the fervor of their converts and allowed them to continue. They even admit to supplying some of the instruments. Káteri Tekahkwí:tha and Wari Teres Tekaien’kwénhtha were among the young women swept up in this movement. A contemporary letter written by Father Pierre Cholenec in February of 1680 undoubtedly describes Káteri, even though she is not identified by name: …there is one especially who

is small and lame, who is the most fervent, I believe, of all the

village, and who, though she is quite infirm and nearly always ill,

does surprising things in these matters. And she would beat

herself unmercifully, if she were allowed to do so. Something

quite important happened to her lately, which Father and I could not

marvel enough at.

While scourging herself as usual with admirable ardor (for she exceeds in this particular all the other women, with one exception of Margaret) and that in a very dark spot, she found herself surrounded by a great light, as if it were high noon, lasting as long as the first shower of blows, so to speak, of her scourging, for she scourged herself several times. Insofar as I could judge from what she told me, this light lasted two or three misereres. 6 One night Káteri asked Kanáhstatsi what she thought was the most painful thing a person could endure, and she said, “fire.” That night, Káteri and Wari Teres decided to place a hot coal between their toes for as long as they could stand it. Just the thought of it was enough to cause Wari Teres to faint. The next day, Káteri revealed to Wari Teres that she went through with it and had the burns to prove it. The next act she did alone, scattering thorns on her bed and laying on them for three nights in a row. Wari Teres found out about this and told the priest, but it was already too late. Káteri was small to begin with—probably no more than 4 ½ feet tall—and malnourished from frequent fasting. Her tiny frame and poor health could not endure such harsh mortification. She died in the odor of sanctity on Holy Wednesday, 1680. Father Pierre writes of a “marvel” that he witnessed upon her death: Due to the smallpox,

Katharine’s face had been disfigured since the age of four, and her

infirmities and mortifications had contributed to disfigure her even

more, but this face, so marked and swarthy, suddenly changed about a

quarter of an hour after her death, and became in a moment so beautiful

and so white that I observed it immediately (for I was praying beside

her) and cried out, so great was my astonishment. … I admit openly that

the first thought that came to me was that Katharine at that moment

might have entered into heaven, reflecting in her chaste body a small

ray of the glory of which her soul had taken possession. 7

Not long after she died, Káteri appeared to at least three individuals, one of whom was Father Claude. The apparitions varied from a simple bedside visit, which is how Wari Teres saw her, to terrifying, prophetic visions of death and destruction, which is how Father Claude saw her. There were whispers among the settlers of New France that a saint had been among them. Miracles were attributed to her intercession. Dirt from her grave, the utensils she ate with, the crucifix she wore—all were known to affect cures. Convinced that he had been in the presence of holiness, Father Claude wrote the first of his many biographies of the young Mohawk woman, followed by Father Pierre, who was equally prolific. Through their writing, the legend of Káteri Tekahkwí:tha, the Miracle Worker of the New World, reached across the sea to France and all the way to the Vatican. A Lily Among Thorns

Káteri Tekahkwí:tha is universally known as the “Lily of the Mohawks.” A Mohawk elder told me that she is called this because after her death, lilies grew on her grave. That may be so, but there is a more mundane explanation. The fleur-de-lys, or “lily flower,” is a heraldic symbol of the French monarchy. Four are depicted in the flag of Quebec. The stylized lily represents the Holy Trinity and the Virgin Mary. Associating Káteri with the lily was the French stamp of approval. It was Father Claude who first evoked the lily metaphor when he wrote, I have up to the present

written of Katharine as a lily among thorns, but now I shall relate how

God transplanted this beautiful lily and placed it in a garden full of

flowers, that is to say, in the Mission of the Sault, where there have

been, are, and always will be holy people renowned for virtue. 8

He was borrowing from the Song of Solomon (2:2) for his analogy: “As the lily among thorns, so is my love among the daughters.” By his hand, another Jesuit’s words were fulfilled as prophecy: a lily was planted on the grave of an Iroquois. Traditional Mohawks, by default, are the thorns in this metaphor, and it’s not surprising that they don’t go anywhere near this story, having served as the contrast to Káteri’s goodness all these years. But there are other thorns to consider. There is the crown of thorns that Káteri chose to share when she consecrated herself to Jesus Christ. There is the bed of thorns that hastened her demise. This brings me to why I believe there was something much more than a simple conversion going on with Káteri Tekahkwí:tha. The Jesuits had to learn Mohawk. They didn’t force us to learn French. They borrowed names and concepts from our creation story to teach us their story. Karonhià:ke, the Mohawk name for Sky World, became the Mohawk word for heaven in the Lord’s Prayer. This was not just a linguistic shortcut, but a conceptual bridge from one cosmology to another. We had something else in common: the belief that it was possible for a human female to unite with a powerful, unseen spirit, and to produce children with mystical powers from this union. This is found not only in our creation epic, but in the story of the Peacemaker and the legend of Thunder Boy. Hearing the story in Mohawk, Mary and her “fatherless boy” must have sounded like one of our own tales. Did Káteri Tekahkwí:tha see herself in that light, as an earthly woman uniting with a Sky Dweller? Or had she been a Sky Dweller all along? Endnotes

1 Greer, A., Mohawk Saint: Catherine Tekakwitha and the Jesuits, Oxford University Press, New York City, 2005, p. vii, xi. 2 Thwaites, R. G., ed., The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents, vol. 46, The Burrows Brothers, Cleveland, 1896-1900, p. 241. 3 Marshall, J., trans. and ed., Word from New France: The Selected Letters of Marie de l’Incarnation, Oxford University Press, Toronto, 1967, p. 326 4 Thwaites, Ibid., vol. 63, p. 177-179. 5 Thwaites, Ibid., vol. 63, p. 193-195. 6 Cholenec, P. “Of Two Other Women,” Kateri, no. 70, Caughnawaga, September 1966, p.8-9. 7 The Positio of the Historical Section of the Sacred Congregation of Rites on the Introduction of The Cause for the Beatification and Canonization and on the Virtues of the Servant of God Katharine Tekakwitha, The Lily of the Mohawks, Fordham University Press, New York City, 1940. p. 306-307. 8 Positio, Ibid., p. 142. |