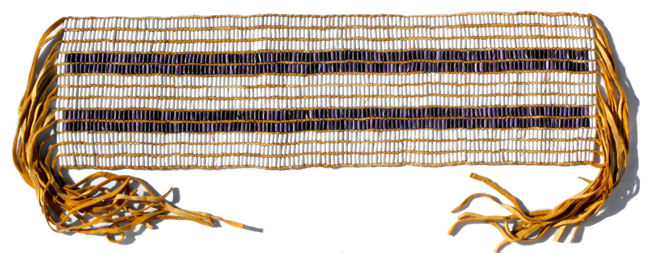

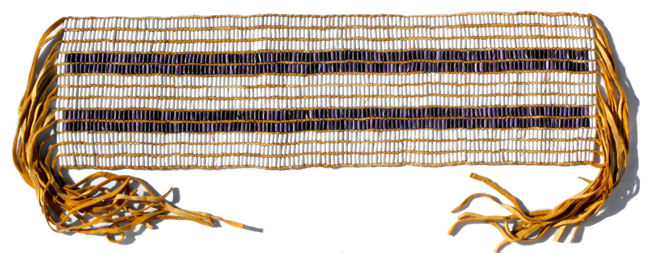

The Two Row Wampum Belt

An Akwesasne Tradition of the Vessel and Canoe

by Darren Bonaparte

(Originally published in The People's Voice, August 5, 2005)

| Not

long ago I had a

chat with

a non-native scholar I met

during my travels. He was interested to know what I knew about wampum

belts and the stories that went with them. In particular, he was

interested to know what I thought about the “two row,” one of the more

famous of the belts. I told him this was considered the granddaddy of

wampum belts to the Iroquois, one which is constantly evoked as being

the guiding principle of our relationships with the colonial powers,

because it sets a symbolic standard of non-interference between the

Iroquois and the colonist: you stay in your boat, and we will stay in

our canoe. Neither will pass laws to interfere with the steering of the

other’s craft. Like a boy who had just learned the truth about Santa Claus and couldn’t wait to tell his friends, this scholar suggested by a slight smirk that this interpretation might not be as old as we Iroquois have been saying. He told me that there is no record of any treaty with the Iroquois where this symbolism is mentioned, not in the Dutch records, the English, or the French. The only symbolism that is mentioned in the documents are allusions to the “covenant chain of peace and friendship,” which started out as a rope tied around a tree but eventually became an iron chain tied to a rock, and later a silver covenant chain. I asked him just how recent our “boat and canoe” symbolism might be, based on his research. He shrugged and seemed reluctant to pin it down, but eventually said it was “fairly recent.” I noticed that he was no longer smirking. I asked him if he had read absolutely everything available about the Iroquois communities, such as the petitions and letters of chiefs and clan mothers of the late 1800. In particular, I asked him if he had read the documentation in the National Archives of Canada about Akwesasne. He admitted that he hadn’t, but had focused his research on the colonial period, two or three centuries earlier. I told him that I had found mention of the “two row” symbolism in a letter written to the Canadian government by the “council of chiefs” of Akwesasne on June 21, 1892, and in this letter it was stated that symbolism was by then already very old. I present this letter with the key points in bold: To

Her Most Gracious Majesty the

Queen,

Madam, Whereas we have taken into serious consideration concerning the affairs touching the welfare of the Seven Nations residing at St. Regis, that we the said Iroquois of St. Regis cannot cease of our original treaty which was sanctioned by His Most Excellent Majesty, the King of England, and the Thirteen Colonies. Madam, it is extremely hard to cease of our original treaty which is to be perpetuated as long as the Sun shall give light and water runs and grass grows, so we cannot see why that we should be treated as minors since the Covenant Chain of Brotherly Love should exist between the Seven Nations of the Iroquois and the English - that the covenant chain should not tarnish but it is to be always kept bright, because we all know that the brightness of the great gold chain of which it is made would admit of no decay. Madam, we have agreed to stand by according to the treaty existing between you and us, - that it is better to be steadfast to our original treaty which was sanctioned by His Most Gracious Majesty, the King of England. Madam, concerning the International boundary line according to our original treaty. That does not interfere with it whatever, but it covers the whole plantation. Madam, concerning the question referred to by all our treaties from the time of discovery to the time of the last treaty - 1st. That the English have made an illustration that they shall abide in their vessel - 2nd - That the Indians of the Iroquois remain in our Birchbark Canoe; 3rd- That the English shall make no compulsory laws for the Indians, but the treaties are to be unmolested forever. Madam, we thought it further necessary to inform Your Majesty that General Henry B. Carrington of the United States has been here to confer with the Iroquois of St. Regis concerning our treaty-rights, - if we, the Seven Nations of St. Regis, do remember of our original treaties from the French to English rule, and also to the rule of the first President of the United States; - that we are justly informed by His Honor Mr. Carrington that our original treaty still exists, and will not be molested or disturbed but will perpetuate as long as the Sun shall endure. But we do not wish to hold of what is not belonging to us - meaning the elective form of trustees, We do not believe that it is calculated to promote our welfare. We all know that all nations adhere to their own form of Government and of their systematic constitutions. Madam, you have now heard our words concerning the treaty existing between us, the Iroquois of St. Regis, and the English; and also you have received our anxiety to maintain our treaty rights, and, moreover, that our desire is that the elective form of trustees should be abolished because it creates impatience and bribery, - meaning the use of Spirituous liquors. Madam, we will now sign our names, so you will know of whom has the majority of the consideration of the Iroquois of St. Regis. This document is interesting not only because it mentions the “boat and canoe” metaphor as being the guiding spirit of all subsequent treaties, but because it presents a political history of the community that incorporates our involvement in the alliance known as the Seven Nations of Canada within a distinctly “Iroquois” identity paradigm. This is something people today have a hard time grasping, as they believe you can only be one or the other. It is true that our ancestors has a council fire that was separate from the Six Nations, but Iroquois political thought processes still governed our actions. In the late 1800’s, the Six Nations and Seven Nations met to discuss the proposed “Indian Act” legislation, the result of which were the petitions they wrote to the Crown. Although the Seven Nations alliance was by then starting to fade away, the chiefs of Akwesasne remembered that it was through this alliance that they took hold of the “covenant chain” with Great Britain at the end of the French and Indian War. In the above document, there is reference to this 1760 treaty as well as to the one signed between delegates of the Seven Nations and New York State in 1796, known today as the “Seven Nations of Canada Treaty,” which is at the heart of our current New York land claim. There is also a reference to the international border through Akwesasne, which seems to confirm the oral tradition that the border was never meant to apply to us. It is interesting to note that this 1892 document states that the “boat and canoe” symbolism may not have originated with the Indians, as Iroquois spokespeople have been saying all these years. As the document states, “the English have made an illustration that they shall abide in their vessel” and “the Indians of the Iroquois remain in our Birchbark Canoe.” Since Iroquois political symbolism has always been focused on land-based metaphors, such as the council fire, the wood’s edge, and pathways between villages, could the “two row” concept be an ancient European seafarer’s tradition that we have adopted over time? A few other interesting factoids about the belt: There are at least four wampum belts that contain the “two row” imagery, which suggests it may have become a common treaty metaphor that was evoked from time to time. One belt ascribed to the Revolutionary War period suggest that it proposed “two roads” the Iroquois could take, the British or the American. The traditions ascribed to the other belts suggest the more well-known “non-interference” interpretation. Although it is common for people today to call the “two row” the kaswentah, this seems to be just a general word for wampum belt and not specific to the belt in question. |